Exterior Space Operation

Opportunities and Operations

Opportunity

Even before systems like ours existed, people were already trying to express themselves—quietly, instinctively—through fitting themself into tools that currently available to them. There is a already large, underserved user base who already exhibit behaviors aligned with us, but are fragmented across platforms. Here are a few indicative reference points that suggest the scale of this group:

- Lurkers and passive expressers: As mentioned in the Expression and Social Platforms section, 49% of U.S. Twitter users are classified as lurkers—users who post fewer than five tweets per month. The U.S. alone has over 100 million Twitter users, with 41.5 million monetizable daily active users. These are users who observe, care, and think—but do not perform.(source).

- Users who already create personal spaces inside closed systems: Some existing applications already let users create personal spaces—but only within the boundaries of a specific platform. Here are two examples:

- Animal Crossing: New Horizons has sold 47.44 million copies worldwide. These users not only bought a $60 game, but also own a Nintendo Switch console.

- Final Fantasy XIV offers in-game housing. In just one week (Apr 26, 2025), tweets tagged

#ff14housinggenerated 2,271 posts, 386,532 impressions, 8,567 likes, 2,128 reposts, and an average of 24.07 bookmarks per post. These users spend effort designing, showcasing, visiting and exploring digital homes.

- Users drawn to ambient, cozy, space-oriented apps: Some casual mobile apps evoke the feeling of owning or curating a space, even if that isn't their explicit goal. Here are two examples:

- Cat and Soup has over 10 million+ downloads and 1.68 million reviews.

- Tap Tap Fish also has 10 million+ downloads and 349K reviews.

Standard and Architecture

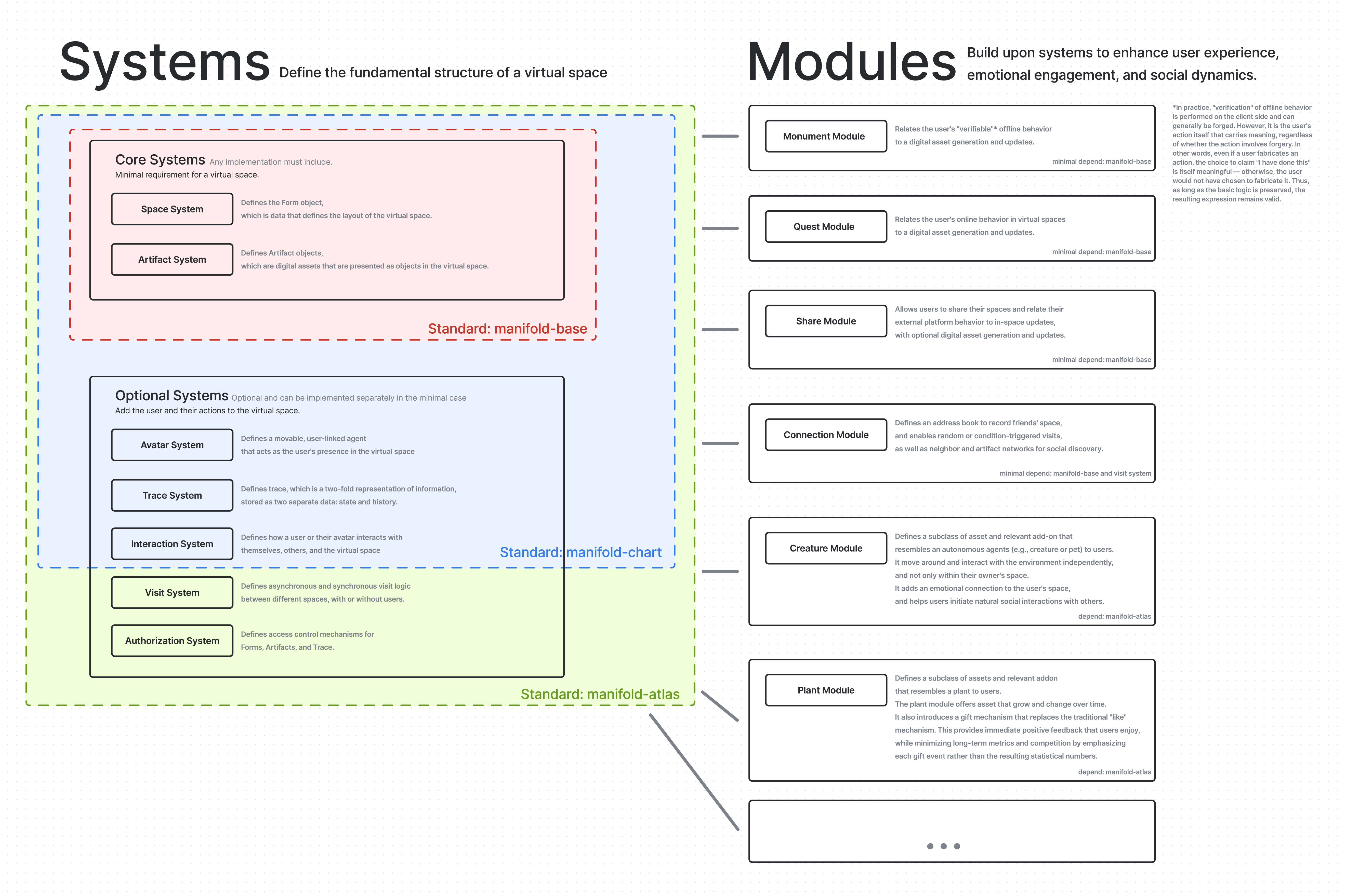

We separate the standard into three parts: the core system, optional systems, and modules.

- Core systems: A standard for defining a virtual space. Any implementation must include the core systems.

- Optional systems: Add the user and their actions to the virtual space. Each optional system can be implemented independently in the minimal case.

- Modules: Build upon systems to enhance user experience, emotional engagement, and social dynamics. A few highlighted modules are listed below:

- Monument and Quest Module: Allow users to craft artifacts from real-life experiences—such as reading a book, visiting a new city, completing an offline challenge, or finishing an online mini-game. These are behaviors users already do or are gently encouraged to try. Onboarding is structured as a welcome quest. Anyone can design their own monument or quest, define its resulting artifact, and deploy it on-chain. We’ll provide many to support the cold start and serve as design references.

- Share Module: Allow users to share their artifacts or spaces through external platforms. Others can visit directly via a link—no sign-up required. This effectively turns other platforms into our timeline feed.

- Connection Module: Allows users to keep an address book for their friends, randomly visit others' spaces, and explore different types of space networks—based on geography, selected artifacts relevance, or selected friends. It also supports multiple types of artifact networks, formed through relevance, similarity, or time.

- Creature Module: Allow users to own pets that grow, remember, and develop preferences, naturally building a connection with creatures they care about. Pets move through space, interact with objects, and leave incidental mark. They can also visit other spaces, leaving their mark and naturally prompting users to visit back and meet new friends.

- Plant Module: Allow users to own plants that grow and change over time (e.g., with the seasons), giving the space a sense of the passage of time. Plants produce small gifts—like leaves, petals, dandelions, or grains. These gifts can be left on artifacts or in spaces when visiting others. They serve as a replacement for traditional "likes": focusing on timely, event-based feedback while minimizing long-term metric-driven competition.

The design ensures that users can intuitively arrange their digital space and interact with artifacts and others through their real-life experiences. Every feature already exists in some form—many are widely used in games or easy to implement individually. The real challenge lies in defining a unified standard that can expand and adapt to future needs.

Architecture

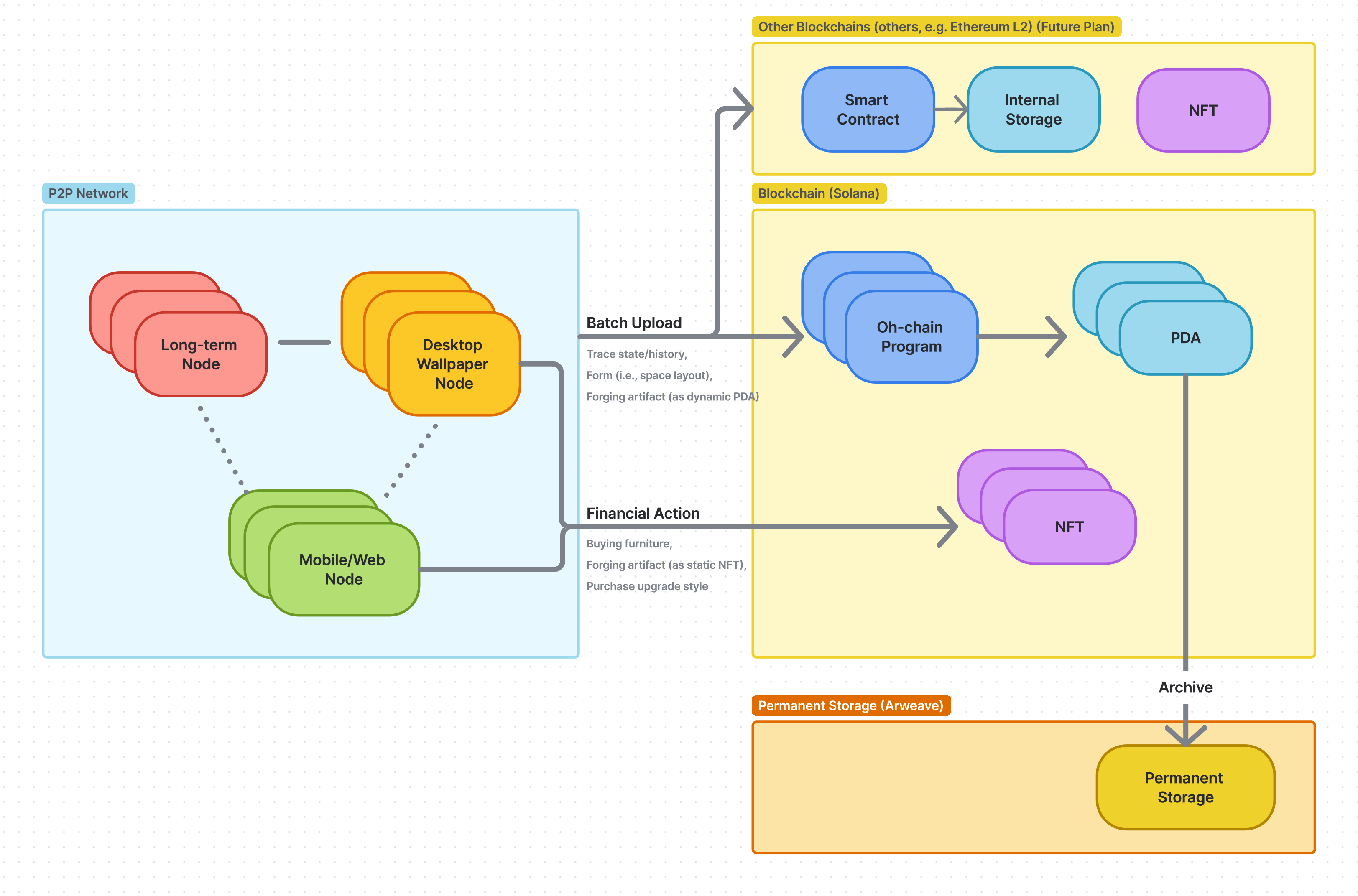

There is a seemingly simple but foundational fact about homes: a person's home belongs to themselves—no one else is inherently involved. This leads to an important realization: all interaction either happens between a user and their own space, or when a user visits another's space. In both cases, the entire process is executed by the user themselves, i.e., the client-side, the personal endpoints.

Beyond that, people also want their personal spaces to be permanent and always accessible, just like their physical ones, but current tools don't work this way. Traditionally, users host content on personal endpoints, which come with limitations: when a user's endpoint goes offline, their personal space vanishes too. Current mainstream solution is to make a transcendent endpoint, a server, to ensure persistent availability, but this fragments and alienates user's self-expression, as it is controlled and monetized by the server owners.

In order to make the user the single source of truth for their own space, we want to construct a server-less architecture. In this model, the user effectively acts as the CPU of the system. The only backend needed is a verifiable, durable storage—a public hard drive. This naturally points to the existing solution, a blockchain.

On the surface, the user is simply moving furniture in their home, or crafting and unlocking artifacts. Behind the scenes, this translates to on-chain assets, state, and history—but all of it is hidden beneath a smooth, natural interface.

To keep this experience smooth, we add a cache layer between the client and the blockchain. This cache layer is made of users themselves, forming a peer-to-peer network. It establishes live connections for visits, temporarily caches history and state, and handles batch submission to the blockchain. In this system architecture, the P2P network acts as RAM.

Importantly, this P2P network is much simpler than traditional ones—we do not require global consensus. The space owner is the sole source of truth for what happens in their space and what they choose to express. Others only need to verify that the recorded events make sense and assist in the batch upload.

For more about the technical feasibility, please visit [FAQ: Challenge].

Cold start, Operation, and Ecosystem

Perhaps the most difficult task is not building the system—but inviting people to begin using it. We do not rely solely on network effects. Each space has intrinsic utility from day one, as a personal place for expression. But we do have a focused plan for cold start and early operations.

Earlier operation: User entering

To invite people into their space, we focus on scene-triggered entry. Many people already have the inherent desire to build a home or preserve a moment. We simply meet them in the right moment—when the desire surfaces—and offer the structure.

- Furniture releases and social media events around space sharing: One powerful trigger is when someone sees another person’s space and imagines what theirs could be. To create that moment, we’ll release themed furniture sets (free or paid) in collaboration with artists, presented in fully staged home scenes (in social media and in app)—like digital IKEA showrooms. We’ll invite creators to share their homes on social media and run community events centered on space sharing and storytelling. Our goal is to let people feel what a home could be, and spark the thought: “I could have one too.”

- Artifact release directly in the community: Another trigger is when we see someone else owns something and feel the desire to own it ourselves. To create this moment, we want to directly showcase artifacts in the community. Imagine a cast member sharing a digital artifact from a show they performed in (or one that’s no longer running), or an indie game developer presenting an in-game model as a commemorative artifact for their players. It could be also a reader sharing a digital book with personal reflections, or a concert fan posting their digital ticket stub. We want to present the relevant artifact in the community where such artifacts already carry meaning, and let people imagine they could own one too.

- City event: We want to create entry points from the physical world—and we will do so by focusing on one city at a time. We won’t run general advertisements. Instead, we want to show people that this is a place where they can obtain a digital artifact or souvenir from their current experience. Moments like visiting a historic bookshop, watching a match, arriving at a landmark—these are already meaningful. We want to work with local managers and business owners to make every potentially memorable experience into an entry point to the system.

City event

We plan to do our first city event in New York City. NYC has a high density of cultural institutions, and more importantly, it’s full of places—big and small—where meaningful moments happen: museums, galleries, historic sites, landmarks, cafés, parks, bookstores, public art... There’s a vivid range of possibility. We can already imagine what kind of digital souvenir we might want after watching Phantom of the Opera (sadly now gone), listening to live music at The Bitter End, or after visiting the Drama Book Shop at 266 W 39th Street, with its flying spiral of ascending books on the ceiling. These are the kinds of moments we imagine people embedding into their digital homes. All of this makes NYC the perfect starting point—and if it succeeds, the same model can be carried to other cities.

Difference from other approaches

If you are still wondering about the difference between what we do compared to others, city event is one outcome of our different approach: A metaverse wouldn’t do this—it wants users to stay inside its world. A social platform wouldn’t do this—it isn’t relevant to their information flow. A traditional game wouldn’t do this—it doesn’t belong to their world logic. This kind of event only feels natural if you start from real life.

Earlier operation: user retention

Our core experience is the building, growth, accumulation, and intertwining of space, which speaks directly to instinctual psychological motives. This experience itself is the foundation of user retention.

- To create a home feeling space, we avoid blockchain or technical jargon entirely. Instead, we use warm, intuitive language that aligns with everyday life. Users don’t need a wallet or blockchain knowledge. Sign-up is seamless—just like any traditional app (Warpcast is a good reference). People can take a look at others’ spaces without signing up.

- To help users start up their space, each user begins with a 16-tile space and can expand to 25 by completing a welcome quest—which also unlocks a wide range of free artifacts for arranging their space. The onboarding flow includes:

- Arranging a space

- Trying the Monument or Quest feature

- Sharing the space on social platforms (others can view without signing up)

- Introducing a plant and harvesting leaves (new users receive a free tree)

- Visiting other spaces through the network system

- Visiting a public space and participating in a simple activity

- Adding a friend (requires both sides to sign up—this is the final quest step)

- To continue building the initial connection between the space and the user, there are quests and events that unfold in steps of days, and unlock new artifacts when completed. Plants and pets also grow in daily steps at the beginning—which makes sense, since they’re still young. This is introduced during the welcome quest, and on the following day, updates will be delivered through push notifications.

- To provide users with the opportunity to get in touch with the community, we will host public events in public spaces. A public space is a long-term maintained area with relevant quests. Users can access public spaces through a button in the app, and they will also be promoted on existing social platforms. In a public space, users can view quest-related souvenirs and furniture, complete event quests to obtain them, or simply sit down with friends next to the Christmas tree and enjoy the feeling of being together.

- To help users build an initial connection with others, we have two mechanisms to make their space visible.

- Some pets will have a preference like “New friends!: Your creature is happy to explore the spaces of newcomers.” These pets will visit new users’ spaces if their layout is valid—providing a minimum guarantee that every new space is seen by at least one pet. Some pets may even visit new users while their owner is online, triggering spontaneous interactions between users. All visiting events will trigger push notifications.

- The random visiting feature and time-based artifact network also prioritize new users by default. For any new user with a valid layout, the system guarantees that their space will be visited by real users. The first visitor will see a message like “You are the first to visit this space,” and may receive a souvenir such as “Space Explorer: Visited 10 new spaces.” All visiting events will trigger push notifications to users.

Ecosystem

We are building an open standard—one that anyone can use, just as we do ourselves.

- Artist can design, launch, and sell their own furniture, souvenirs, avatar templates, and fashion items. Existing NFTs can be used out of the box, and artists can optionally add relevant metadata to improve compatibility. We will provide tools and guides to help artists turn their work into artifacts compatible with the standard, and guide them through launching and deploying on-chain. They can sell independently through their own sites or apply to list their items in our app.

- Users can make their own spaces public, design online quests, host offline events, or create their own mementos. The Quest and Memento modules will help validate user behavior and distribute souvenirs to participants or reward those who complete specific tasks—just like we do in public spaces or city events. But users can go further: they might create a personal archive, a roleplay inn, a digital exhibition, an online amusement park, and more. We will provide tools and documentation to support them. They can promote their spaces independently or apply to list them in our app.

- Developer can extend our standard. We already have many ideas that are possible given our current architecture: they can define new interactions, set up asset leasing, build TRPG or RP simulators, or even create AI companions—and many other possibilities we haven’t thought of yet. All of these new modules will be dynamically loaded when used, as they are code stored or run on-chain.

- Other platforms can enhance their connection with users. Any platform can help its users create artifacts with information related to the platform. In the future, we will work with external platforms, like reading apps, to help them create or edit artifacts in user spaces. Information such as movie reviews or trip plans can flow from other platforms into user spaces and become artifacts, carrying metadata and links from the original platforms. This expands the entry point to space and also frees the information from existing platforms, bringing it into the user's life.

Business Model

We believe all parts of the system should be accessible without requiring users to pay—because that’s the only way to create an open and universal online space. Our approach to monetization is to enhance the experience for those who want more, not to restrict it for regular users.

We think of ourselves as having two closely connected parts:

- One part is the standard and its reference implementation.

- The other part is operational, which is the first and largest user of that implementation and its ecosystem.

The operational side focuses on community management, partnerships with artists and business owners, and the creation of basic furniture, quests, and mementos—along with optional upgrade paths. Our revenue sources include:

- Paid artifacts: While many furniture items, creatures, and plants can be unlocked for free through quests or monuments, there are also exclusive pieces we design ourselves or co-create with artists that can be purchased directly.

- Upgrades to mementos: Many mementos can be visually upgraded without altering their meaning. For example, a digital souvenir earned by completing an exploration activity at a landmark might be a stylized 3D model of the landmark. Users could optionally unlock versions with a night-time lighting effect, an oil-painting style render, or a dramatic storm effect.

- Pet-related items: Some furniture will influence how pets behave in the space. There may also be optional items for rapid pet training (e.g. shortening training from subtle influence to one day), or items that temporarily change a pet’s preference or appearance—such as special food that gives visual effects or alters social behavior.

- Brand and IP collaborations (future): We can collaborate with companies or IP holders to create and sell branded artifacts, design themed spaces, co-host special events, or feature brand-related content inside public spaces.

TILE Token

A quick calculation shows that the current cost of using blockchain—including PDA storage, uploading to Solana, and moving long-term content to Arweave—is approximately $0.80 per user per year. The goal of the TILE token is to close this loop: by using TILE, the system can cover its own blockchain costs.

TILE is a utility-only token. It functions as the “floor” for placing objects in a user’s space. Every user receives 25 free "TILE"s (non-transferable) as a starting allocation. Any object placed in the space must be placed on a TILE. Additional TILEs can be acquired in the following ways:

- Minting: TILE will be periodically available for "minting" in limited quantities at a flat cost. Minting is only open to users who have completed the welcome quest and expanded to 25 "TILE"s. This creates an accessible entry price while allowing the secondary market to determine further value. The mint cost will around ~0.005SOL.

- Contributing to the P2P network: Users can earn TILE by supporting the network. This includes running their device as a desktop wallpaper node (user who set their space as wallpaper, and keep their computer on), or maintaining a long-term node, both assist with batch uploads. If you think of the P2P layer as another kind of blockchain, this is a form of proof-of-time-connected utility.

A noteworthy property of TILE is its nonlinear demand curve: users pay linearly to obtain TILEs, but human perception of space tends to grow quadratically (e.g., a 4x4 room feels much smaller than a 6x6). This means that users with larger spaces tend to need disproportionately more TILEs to achieve further meaningful expansion.

Close this loop: Spending

Please note that the following plans are long-term and might change in the future. We will need to consult an expert about their economic structural feasibility.

Now we are going to talk about how to spend the TILE token. This relies on a basic fact about non-native on-chain tokens: each such token is actually “stored” using a small amount of the native currency—in our case, SOL.

We will create a treasury public account, which can only spend its balance in two ways:

- To pay on behalf of users when data is uploaded to the blockchain through the P2P network

- To reward users who contribute to the P2P network

When a user "mints" TILE, a portion of their SOL (for example, 20%) will be transferred to the treasury public account. The remaining 80% will stay as the “storage” amount for the TILE token itself. This setup enables two key actions:

- A user can burn their TILE and get back 80% of the SOL they used to mint it

- A user can spend TILE elsewhere in the system; this transfers the TILE to the treasury account, which can then convert it back to SOL and use it to cover network blockchain costs

This creates a circular flow, but the loop is not yet complete—because at this stage, there are no other spending uses for TILE. These will be introduced in Phase 2, once the system has broader adoption.

Until then, we will monitor the treasury account closely and make sure it holds enough SOL to support ongoing blockchain operations.

Phase Two

Phase Two aims to complete the cycle by allowing users to spend TILE—primarily through renting land—thus moving TILE into the treasury public account and supporting the system’s blockchain costs. This phase will only begin when the system (personal space) is already widely adopted, as it depends on having enough users to sustain it.

We begin with what we offer to users: our standard is a standard for visual space, and one use of it is to connect different spaces together—for example, to enable chunk loading for performance. We extend this into a LAND module.

The LAND module simply adds neighborhood metadata to each space. Users can rent a fixed-size chunk and connect it with other users’ chunks—if all neighboring users agree. Each user can build on their own chunk, forming physical links to others and gradually creating shared landscapes and collective geography.

Within each user’s chunk, they can place a door that leads to their personal space—the one they built in Phase One. They can also place windows, doors, or balconies as immersive portals connecting the chunk and their home.

Users can now literally walk from space to space; their personal space gains additional context. Communities can self-organize by clustering compatible spaces. This also enables land economics—for example, adjacency to popular spaces could be more valuable. And it introduces a new layer of space discovery, in addition to the existing network mechanism.

Importantly, this builds on existing structures:

- For the standard: it only requires adding neighborhood metadata.

- For the architecture: the chunk owner remains the single source of truth, nothing would be changed.

- For rendering: it’s standard chunk-loading logic, used by nearly every performance-optimized game.

- There are existing rendering solutions for immersive portals that are widely used in games like Minecraft.

This creates a natural, ongoing reason for users to spend TILE—to rent chunk of land. When they do so, the TILE is transferred to the treasury account, converted back into SOL and used to cover blockchain operation costs. At the same time, the mint cost of TILE would be dynamically adjusted based on the number of active users (which can be found by checking how much space is needed for blockchain uploading) and the balance of the treasury account.

Roadmap & Team

Currently, this information is not publicly available. Please contact us for more information.